<aside> 🍃 “Two spices, one tree: an analogy. About how the fineness of life cannot be uncoupled from its finitude?” (McLarney, 2019)

</aside>

This is a story of nutmeg: How did its cultivation begin, how it pertains to Singapore and how it came to be a staple spice, tucked in the pantry of almost every household.

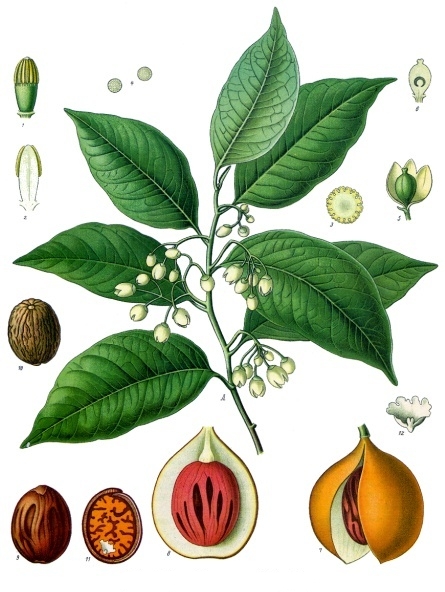

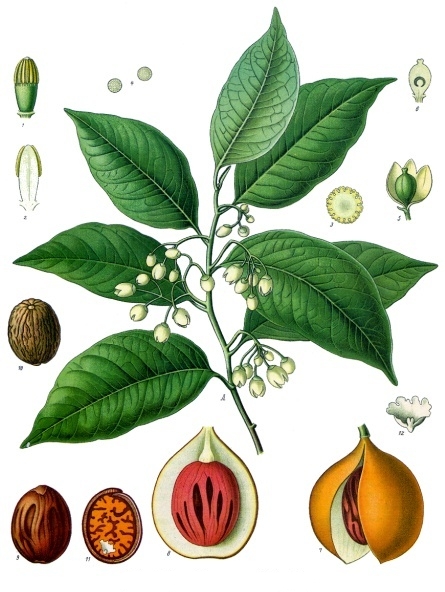

The true nutmeg is endemic to the Banda Islands, later known as the Spice Islands, a group of islands in present day Indonesia (Gils & Cox, 1994). This is a tree cultivated for two spices — nutmeg and mace, from the seed and seed aril respectively. The Myristica fragrans was found only in this part of the world, a gem hidden from European sight, at least at first. The first recorded mention of nutmeg by the Europeans seem to be in a poem by Petrus D’Ebulo, written in 1195, about how the scent of nutmeg was used in the coronation of Henry VI (Ridley, 1912). By the 17th century, knowledge of the spice in Europe was widespread, though the rare spice remained inaccessible, since 500 grams of nutmeg was valued at about three sheep (Ridley, 1912). Nutmeg’s high value could be attributed to the belief that it can help ward off plague (Abourashed & El-Alfy, 2016) —rampant at the time. Naturally, desire for the control of the spice trade arose.

Myristica fragrans illustration by Franz Eugen Köhler in Köhler's Medizinal-Pflanzen, 1897

In 1511, the Portuguese conquered Melaka. Shortly after, the Portuguese set foot on the Banda Islands, via large ships that frightened the locals. Such began the Portuguese domination of the spice islands, who enjoyed riches as the price of Nutmeg continued to rise (Villiers, 1981). The Portuguese faced resistance from the locals, who welcomed the Dutch when they later arrived in 1599. The islanders thought the Dutch would rid their land of the Portuguese they dreaded. However, in 1605, the Dutch seized control of Portuguese forts and in 1609, turned against the locals, imposing a treaty on them, securing their monopoly in the spice trade. Further resistance from the locals led to drastic measures by the Dutch, who culled the local population (Villiers, 1981). The Dutch had managed to plant their flag, in the form of orderly rows of Nutmeg trees. For good measure, the Dutch also began coating Nutmeg with toxic lime, to prevent them from successful sprouting elsewhere (Raden, 2016).

The Dutch had control of all but one of the nutmeg-growing islands —Pulau Run, the smallest of the Banda Islands. Fearful of the Dutch, the natives had, in 1616, pledged allegiance to the British. The British defended Pulau Run from the threat of Dutch East India Company, but only for over two years, before the Dutch successfully seized control of the island and destroyed the nutmeg trees there. Later in 1654, after the first Anglo-Dutch war, the Treaty of Westminster saw that Pulau Run was returned to the British. However, in the Treaty of Breda after the second war (1665-1667), the island was returned to Dutch control.

Later in 1810, making use of Dutch interregnum of the Napoleonic War, the British were able to infiltrate the Banda Islands and smuggle nutmeg seedlings and start nutmeg plantations of their own (Gils & Cox, 1994). A home to such plantations is the island of Singapura. Raffles saw the potential in Singapore to become a spice island and help the British empire break the Dutch monopoly on spices. An avid botanist, Raffles started an experimental garden at what is now Fort Canning Hill, where he grew nutmeg. Later in the 1830s and early 1840s, nutmeg plantations took off when the spice promised growers bountiful profits. Nutmeg plantations flourished in the Orchard area, where hills were named after large plantation owners, including now familiar names like Oxley and Prinsep (Low & Pocklington, 2019).

Sculpture titled ‘Nutmeg & Mace’, by Kumari Nahappan (2014)

Sculpture titled ‘Nutmeg & Mace’, by Kumari Nahappan (2014)

Alas, all good (subjective of course) things come to an end. According to Jaffrey’s (1860) account, Nutmeg trees here began to have “...a yellow sickly appearance of the foliage, the branches …showed symptoms of decay, and the fruit dropped off before ripe.” Hit by a mysterious blight, plantation owners complained that they would wake up to decaying trees that produced light crops and inferior fruits. Some were baffled and others blamed the soil, ruined by the nutrient-sapping plantations themselves (Ridley, 1912).

It was only years later that the cause of the mysterious blight was understood. Henry Nicholas Ridley detailed his findings in his book, Spices (1912). By 1866, this disease has almost wiped out nutmeg trees and the possibility of their cultivation here. The cause — a beetle. Ridley described their small, white grub that burrows into the bark of the nutmeg tree, killing the tree, bit by bit. Often, when any signs of attack are evident, the tree is already too sick to be saved. The Hyledius cribratus, a bark boring beetle less than 0.5cm large had born holes into the trees, eventually damaging their roots and leaving the trees to die, inviting other wood-eating insects to feast on the dying matter. Planters abandoned their once prized trees. The nutmeg craze was to die with swathes of land, trespassed by creeping secondary vegetation (J. & Chay, 2004).

In 2018, the largest producer of nutmeg is by far Indonesia, supplying 46.1% of the global supply (Observatory of Economic Complexity, 2019). In the pantry at home, our tiny supply of ground spice came from nutmeg grown in Indonesia, changed hands in Australia and made its way to Singapore in a tiny glass bottle cased in plastic, which I proceed to open and tap into my pancake batter.